Questions from visitors

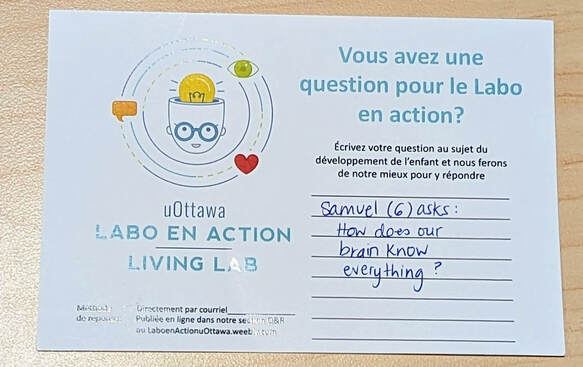

Living Lab visitor Samuel (6) asks: "How does our brain know everything?"

Thank you for your question Samuel! It does seem like our brains know more than we realize, sometimes, doesn't it? Well, we know from the research that we have done in the lab here, that our brains notice things and then store certain details for later. Hopefully, we can remember all of the details when someone asks! And hopefully, what we remember is correct.

Now, your question is a great one because it asks about how this magic happens.

Here is one explanation that will hopefully help you on your path to "know" how your brain knows everything!

The structure: Inside our skulls, our brain is composed of different lobes, or areas. Each lobe has a different function, or job, such as listening, reading, drawing, speaking, doing math, etc. And the brain itself has two sides, called hemispheres. These hemispheres are like a mirror reflection of each other because they have the same lobes, so there is a left lobe that is able to hear and a right lobe that is able to hear (these are called the temporal lobes), etc. This is a great survival design because if one side of the brain gets damaged, then the other side can usually still do the job!

The function: The lobes consist of many, many, many important cells called neurons. Neurons do all the communication in the brain, by receiving information such as "Oh! I hear a sound!", to passing that information on, such as "Do I know that sound? Hey, neurons in the temporal lobe...do you know this sound?", to passing the information to parts of the brain that would react, such as "Yes! I know that sound. That's my name. Uh oh. Mom is calling my name...I should respond. Hey, frontal lobe, you should respond because Mom is calling us. Say 'yes'". All of this information is passed easily from one neuron to another because the middle parts of neurons are like wires and their only job is to pass on that information as quickly as possible. They can transmit information as fast as 270 miles per hour, which is faster than most cars. In fact, only recently has a race car been able to travel that fast!

So you see, Samuel, our brains are kind of like computers as information goes in and is passed along wires (the axonal bodies of neurons) until that information reaches the most appropriate cells in the appropriate lobe. Those neuronal cells will understand and then react. We hope that this (long) explanation has answered your question!

Thank you for your question Samuel! It does seem like our brains know more than we realize, sometimes, doesn't it? Well, we know from the research that we have done in the lab here, that our brains notice things and then store certain details for later. Hopefully, we can remember all of the details when someone asks! And hopefully, what we remember is correct.

Now, your question is a great one because it asks about how this magic happens.

Here is one explanation that will hopefully help you on your path to "know" how your brain knows everything!

The structure: Inside our skulls, our brain is composed of different lobes, or areas. Each lobe has a different function, or job, such as listening, reading, drawing, speaking, doing math, etc. And the brain itself has two sides, called hemispheres. These hemispheres are like a mirror reflection of each other because they have the same lobes, so there is a left lobe that is able to hear and a right lobe that is able to hear (these are called the temporal lobes), etc. This is a great survival design because if one side of the brain gets damaged, then the other side can usually still do the job!

The function: The lobes consist of many, many, many important cells called neurons. Neurons do all the communication in the brain, by receiving information such as "Oh! I hear a sound!", to passing that information on, such as "Do I know that sound? Hey, neurons in the temporal lobe...do you know this sound?", to passing the information to parts of the brain that would react, such as "Yes! I know that sound. That's my name. Uh oh. Mom is calling my name...I should respond. Hey, frontal lobe, you should respond because Mom is calling us. Say 'yes'". All of this information is passed easily from one neuron to another because the middle parts of neurons are like wires and their only job is to pass on that information as quickly as possible. They can transmit information as fast as 270 miles per hour, which is faster than most cars. In fact, only recently has a race car been able to travel that fast!

So you see, Samuel, our brains are kind of like computers as information goes in and is passed along wires (the axonal bodies of neurons) until that information reaches the most appropriate cells in the appropriate lobe. Those neuronal cells will understand and then react. We hope that this (long) explanation has answered your question!

Presentations

March 2024 Maïsha Morneau presented a poster at the Psycholinguistic Shorts Conference at the University of Ottawa. This poster presented the results of our Knowledge Mobilization research project. Congratulations and great job, Maïsha!

November 2023 The uOttawa Living Lab presented and joined a round table discussion at the First Canadian Summit on Living Labs, co-organized by the McGill-University of Montreal-CRIR Living Labs in collaboration with ENoLL, the European Network of Living Labs. This event brought together Living Labs, innovators, strategic partners, and decision-makers from Canada and abroad to exchange ideas and foster potential collaborations. Presenters: Lab Directors Tania Zamuner and Chris Fennell.

October 2019 Congratulations to the members of the Living Lab who presented at the Cognitive Development Society Conference in Louisville, Kentucky, USA. These members include: graduate student researchers Gladys Ayson, Bronwyn O'Brien, and Marie Drolet; Post-doctoral researcher Joshua Rutt; and lab director Cristina Atance.

November 2023 The uOttawa Living Lab presented and joined a round table discussion at the First Canadian Summit on Living Labs, co-organized by the McGill-University of Montreal-CRIR Living Labs in collaboration with ENoLL, the European Network of Living Labs. This event brought together Living Labs, innovators, strategic partners, and decision-makers from Canada and abroad to exchange ideas and foster potential collaborations. Presenters: Lab Directors Tania Zamuner and Chris Fennell.

October 2019 Congratulations to the members of the Living Lab who presented at the Cognitive Development Society Conference in Louisville, Kentucky, USA. These members include: graduate student researchers Gladys Ayson, Bronwyn O'Brien, and Marie Drolet; Post-doctoral researcher Joshua Rutt; and lab director Cristina Atance.